|

|

|

|

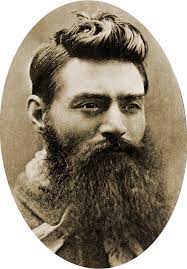

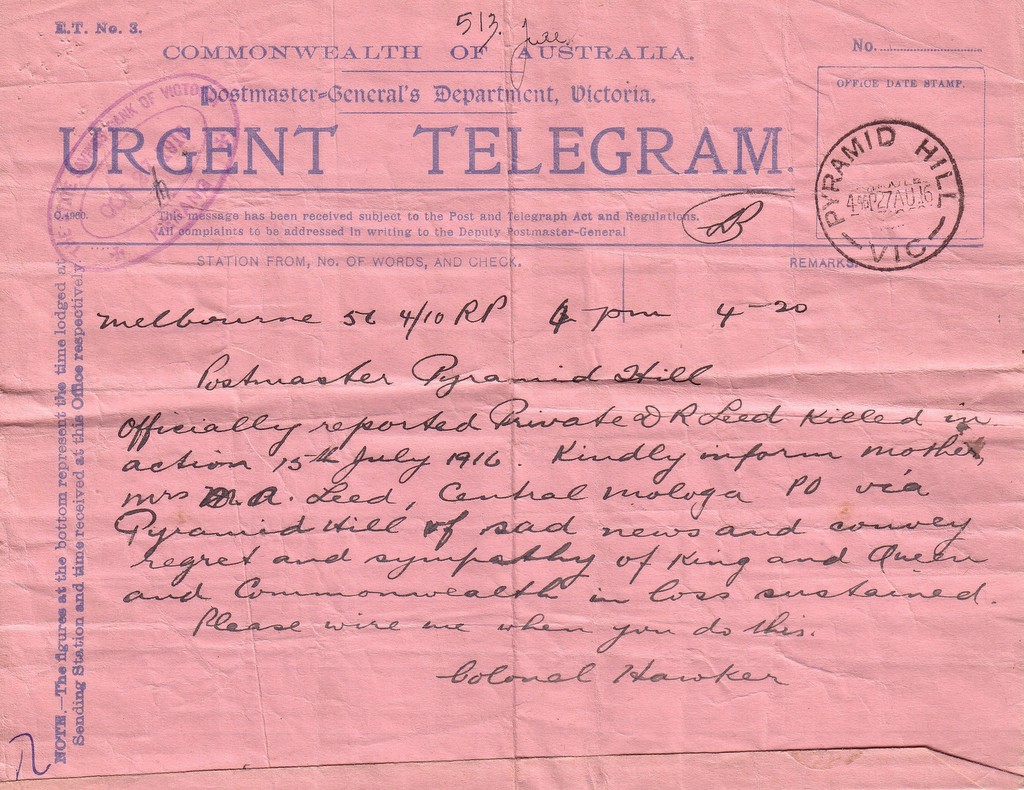

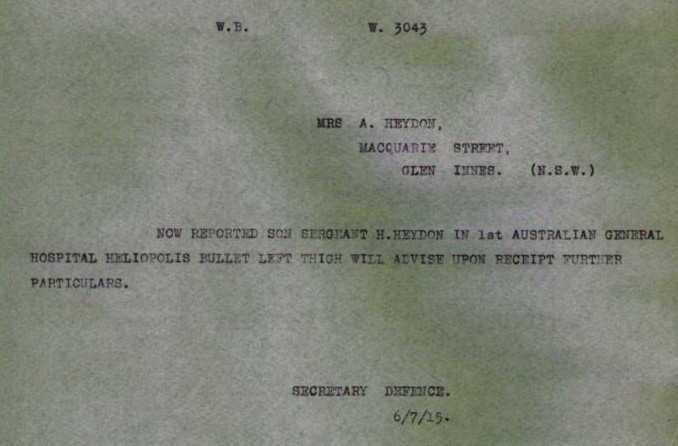

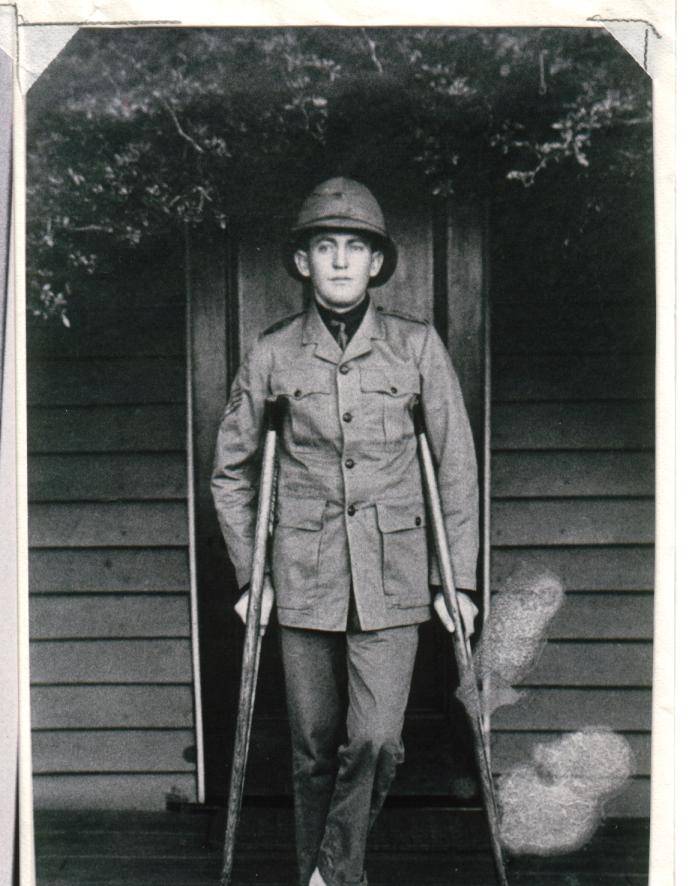

Heydon Family TreeWelcome to the journey of the Heydon and Learmont lines in Australia. While this account is written and compiled by Ian Heydon, grandson of William Frances Heydon, much of the pre-WW1 Heydon data is thanks to research by Kay Cockram, granddaughter of William’s brother, Cleave Heydon. There is a famous song that says there is a track winding back, along the road to Gundagai. This track winds forward to Gundagai to see the arrival of Ian David Heydon in 1954 and Margaret Jill Heydon in 1958. The track starts in Germany, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. It is usual/easier to follow the male lineage but let’s go way back to some of the first females in Australia who became Heydons… AMY HEYDON (KNEIPP)  The German lineage comes from Johann Baptist Kneipp. He took the name ‘John’ after arriving in Australia and settling in Glen Innes.  He married Caroline Utz (1842-1924) in Germany. They had 11 children and 69 grandchildren. But for Scottish inventor, John Logie Baird, coming up with television as a nightly activity, the population explosion could have been enormous! One of the 11 kids was a daughter, Amy, who would marry William Heydon in 1882 and have 8 children including William Francis Heydon from Tumut.  Incidentally, Caroline’s brother, Frederick, was mayor of Glen Innes from 1881 to 1884. 1884 was the year William Francis Heydon was born. Fred had 10 kids of his own. Rabbits. There’s also a mayor on the Learmont side and both sides throw up men with various occupations. In this distinguished and motley mix, you will find farmers, graziers, butchers, public servants, musicians, government officers, alcoholics, mental patients, drapers, publicans, military men and a minister of religion. Most of the womenfolk were too busy having babies and bringing them up to work. WILLIAM FITZGERALD HEYDON  Amy’s hubby William’s father was William Fitzgerald Heydon and he was born in 1812, in Athy, County Kildare, Ireland. In case you are wondering what was happening in the world when ol’ William Fitzgerald came into it in 1812, apart from an overture bearing that year in the title from Pyotr Illyich Tchaikovsky… 1812 to 1840s NEWS UPDATE Napoleon Bonaparte was running around picking up countries like it was a game of Risk and the Duke of Wellington was about to show him that taking Waterloo would be taking one too many risk… Lord Byron was busy making speeches in the House of Lords, writing poetry and carving his name into an ancient ruin at Cape Sounion in Greece. Been there, seen that. It’s amazing how fame can take you from being a vandal to a tourist attraction. On May 11, 1812, the British Prime Minister, Spencer Percival, was assassinated in the foyer of The House of Commons by John Bellingham. Not many people know that assassinations happened outside America. Fewer people know that descendants of both Percival and Bellingham would also be elected to parliament, at the same time. Awkward! George III was King of England and Lachlan Macquarie was Governor of New South Wales. In November that year 40,000 Spanish dollars (coins) arrived in Sydney on the Royal Navy Ship Samarang. To prevent the money being used outside the colony, holes were punched in them and ‘holey dollars’ became Australia’s first official currency. Moving on to the 1840s, around the time that William and Sarah Heydon hit our shores… Queen Victoria was monarch… the Governor of NSW was Sir George Gipps… explorers like Charles Sturt and Ludwig Leichhardt were out and about, exploring… literary types in London were asking “What the Dickens?”… and groovers were bopping along to the Industrial Revolution Sultans of Swing… Yep, Giuseppe Verdi, Felix Mendelssohn and Richard Wagner were belting out some catchy tunes… Oh! And in some family trees far, far away Thomas Flanagan had just married Bridget McDaniel nee Kenny in Lancashire and John Clark was born in Whitby… These clans would merge and merge again when Ian Heydon and Anne Flanagan marry in 1979. William Fitgerald Heydon’s parents were probably William and Julia Heydon (Julia’s maiden name was Fitzgerald) and the younger William migrated to Australia in either 1842, 1843 or 1844. There is a record of a ‘Mr Heydon’ departing Ireland on the Dublin and arriving in Port Phillip, Sydney on both December 13, 1842 and January 18, 1843 and we get the first name of William with surname Heydon arriving on the Royal Saxon in 1844. He arrived in Sydney in the 1840s and headed north to the Land of the Beardies, as the area around Glen Innes was known. It is also known as ‘Celtic Country’. Legend has it that the Land of the Beardies got its name when two stockmen and former convicts, John Duval & William Chandler rode north in the early 1840s. They were the first known white men to see the expanse of ‘unexplored’ grazing country to the north of Armidale. They wore long beards and gentlemen from elsewhere looking for suitable land for stock were recommended to apply to ‘the Beardies’. There are two other possibilities. The loach, a local fish resembling a European catfish, is referred to in northern England, Scotland, and parts of southern Queensland as a ‘Beardie’. And, as the area was settled by many Scots, they would have bought with them their sheepdogs known as the Bearded Collie or ‘Beardie’. But the two blokes with the beards story makes more sense. William Fitz was handy on a horse and well-educated, which in those days meant he could read and write. Whole documented to be ‘protestant’, he may have been studying to be a priest in Ireland. He was a Greek scholar and coached pupils in Latin in Glen Innes. According to his obituary, he arrived in Glen Innes in 1849 with a mate, Sandy Meston, and was engaged in moving horses from the Richmond River to the Murrumbidgee. He died in the same year as Captain Moonlite and Ned Kelly, 1880. William was 68, Moonlite was 37 and Ned was 25.  Such is life. William died, at home, a six-year-old brick house in East Street, Glen Innes after medical attention was sought by daughter, Sarah. Dr Clayworth designated the cause of death to be ‘pneumonia anaemia’ so there you go, a documented case that men can suffer badly from colds! That’s the cause of death on the 1880 death certificate. He died on August 23 and was buried the day after.  One can imagine that stonemasons allowed a grave to ‘settle’ over time before adding a headstone to the plot and that may be why the date of death on the headstone is 1881 rather than 1880. A grave mistake perhaps? Or a monumental error? Or even someone in need of temperance? You see, William was a mover and shaker in the temperance movement, which was somewhat ironic as he was a publican. He was also, at various times, a road contractor, a storekeeper, a carrier, an assessor for the municipality and a butcher. He once advertised a position of butcher with the rider, “No lushingtons need apply.” That word would have been the origin of the word ‘lush’. Also on this headstone are his sons Daniel (1873), James (1907) and wife Sarah (1923). In the same cemetery are his son, William (1897) and daughter Annie Eliza (1860 – 1954) – she married Frederick Doust in 1885 and had seven children. Two of the boys were killed in action in World War One. The day after William’s death, this obituary appeared in the Glen Innes Examiner… Death of Old Resident It becomes our painful duty to chronicle the death of Mr William Heydon which sad event took place yesterday morning at his residence in East Street Glen Innes. Deceased has been confined to his room for the past eight or nine days suffering from a severe cold. Although he complained of being very unwell and medical advice was sought yet it was never imagined for a moment that his illness was of such a serious nature, and when the rumour was circulated and he had breathed his last many were the expressions of heartfelt regret. Deceased leaves a widow and a large family of children most of whom however are grown up. Mr Heydon we understand has been a resident of New England for over 30 years and some 20 years ago he carried on business as a publican on the site where now stands only a solitary willow, on the Clarence Road to mark the spot where at many a pleasant hour was spent by old hands, most of whom have since joined the great majority. He was also in business some years ago as a butcher. Deceased who was deservedly respected was 68 years old and was a prominent and indefatigable leader of the temperance cause for many years past. His funeral takes place this afternoon at half past two. Of course, there are Heydons mentioned historically way before half-past-two on August 24, 1880, but it is easier to trace family trees going in reverse than taking pot luck on following a coincidental surname from the past and going forward with fingers crossed. Mind you, the name Heydon dates back to 1086. Back to the women… William married twice. The first wife, Mary-Jane Rodgers was born in Omagh, County Tyrone in Ireland, in 1831 and was nearly 20 years William’s junior. They married in Rouchel in the Hunter Valley in 1848 when she was 16 and he was 35. They had two kids – a daughter, also Mary-Jane, was born in 1849 and son, John, was born in 1851. Mother Mary-Jane died that year, aged 19 or 20. Might have been in childbirth, which was not uncommon. We don’t know a lot about those two children but we assume they were raised by the Rodgers family and William moved on. There is a record of John being christened in the Parish of St Peter, Armidale on the same day as his cousin, Alexander Thomas Rodgers. We do know that Mary-Jane died in 1886 and John died in 1928. William did move on and he married Sarah Hutton. Sarah was originally from County Down, Inch Cork, in Ireland and arrived in Australia aboard the good ship Percy in 1841, aged eight years. Sarah was 20 and William was 40 when they tied the knot in Stonehenge in 1853. They had ten children, namely: William (1854) James Donald (1856) Daniel Maxwell (1857). He died aged 15. Robert (1859). He married Amanda Powell. Annie Eliza (1860). She married Frederick Doust. Andrew Cleland Kealy (1862) Sarah (1863). She married V.H. Williams. Jemima Maria (Dolly) (1866). She never married. Frances Edward (1868). He married Elizabeth Baker and Catherine Rainiers after Elizabeth died. Rebecca Alice (1872). She never married. Sarah joined her husband in the cemetery in 1923. She was aged 90 and had been a widow for 47 years. Sarah saw one son, Robert, and fifteen grandchildren go off to fight in World War One, three of them killed in action, four wounded and returned and others injured physically and psychologically. Let’s jump ahead for a bit and look at a few who went to the war… THE PINK TELEGRAM  When a soldier was killed in action, the usual practice was for the deceased’s designated next of kin to receive a ‘pink telegram’ to inform them of their loved one’s death. In the case of Frank Heydon Williams, the next of kin weren’t officially notified. The ‘pink telegram’ was a telegraphic message sent from one post office to another and then written or typed on a flimsy sheet of pink paper, put into an envelope, and delivered to the relative. Sometimes the telegrams were delivered by a lad on a bicycle; sometimes they were delivered by the parish priest or minister. Wives, mothers and neighbours were constantly monitoring the streets for the approach of either but sometimes the actual telegram would go missing in action. This happened when Frank Heydon Williams was killed at Pozieres on the Western Front. This article from the Glen Innes Examiner dated September 29, 1916: It is our sad duty to relate that another Glen Innes soldier in the person of Private Frank Heydon Williams has fallen on the battlefield in France, death occurring as far back as July 24 last. Up till Friday morning his relatives had received no intimation whatever from the military authorities that the young soldier had been killed, and one can scarcely imagine what a tremendous shock it was to his parents and sisters, when it was conveyed to them by letter on the morning in question. Miss Williams was simply overjoyed at the sight of receiving a letter from her other soldier brother, Bob, but on opening and reading it discovered that Frank was killed in France on July 24. She was quite naturally simply prostrated with grief, and for a while unable to inform her father of the sad and sudden news. He was shot through the heart with a piece of shrapnel, and died almost immediately.  Frank Heydon Williams has no known grave but is honoured on the wall at Villers-Bretonneux in France and at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. Frank was a shop assistant when he enlisted as a Private on September 6, 1915 in the 2nd Battalion. The troops embarked from Sydney in December and Frank was a 27-year-old Lance-Corporal when he was killed seven months later. His next of kin were Humphrey Vaughton Williams and Sarah Williams (nee Heydon). The other two grandsons not to return were the sons of Frederick Doust and Annie Eliza Doust (nee Heydon). Lieutenant Harold Doust was a 28-year-old draper when he enlisted as a Private on August 19, 2015. His unit, C Company, 30th Battalion, embarked from Sydney on HMAT A72 Beltana on November 9, 1915. Harry had been promoted to Lieutenant when he was killed in action on September 30, 1918 at Navoy in France and he is buried at Bellicourt British Cemetery in France (Plot IV, Row S, Grave No 6). He was also wounded twice and awarded the Military Cross for bravery. The citation reads: “For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during an attack. He took forward a patrol, and captured three machine guns and sixteen prisoners, killing several of the enemy, with only three casualties on his own side. His fine action greatly helped the advance, and throughout the operations he did splendidly.” Lieutenant Frederick Herbert Doust was Annie and Humphrey’s other son to pay the ultimate sacrifice. He was a 21-year-old shop assistant when he enlisted as a Private on September 18, 1914. His unit, A Company, 13th Battalion, embarked from Melbourne on Transport A38 Ulysses on December 22, 1914. On that ship was his commanding officer, John Monash. Frederick saw war service in Egypt, at Gallipoli and on the Western Front. He was killed in action on September 26, 1917 at Polygon Wood, Ypres in Belgium (Polygon Wood 1917 below). He has no known grave but is honoured on the Menin Gate Memorial at Ypres (Panel 17.) Having been promoted to the rank of Lieutenant when killed, Frederick was also awarded the Military Cross for bravery. The citation: “For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. Whilst leading reinforcements to the front line he was severely wounded by enemy shell fire. In spite of this, however, he guided his men to cover, and when shelling stopped again led them forward to the trenches, handed them over to his company commander, and then collapsed from loss of blood. No praise can be too great for his pluck and devotion to duty.” The Menin Gate Memorial (so named because the road led to the town of Menin) was constructed on the site of a gateway in the eastern walls of the old Flemish town of Ypres. The Memorial was conceived as a monument to the 350,000 men of the British Empire who fought in the campaign. Inside the arch, on tablets of Portland stone, are inscribed the names of 56,000 men, including 6,178 Australians, who served in the Ypres campaign and who have no known grave. It was not uncommon for soldiers to receive rapid promotions, simply because of attrition in the ranks… and it was up to the junior officers and senior NCOs to lead the other ranks out of the trenches and into the fray.  Yes, three of the fifteen young men in the Heydon clan were to not realise their potential… not to have a civilian career… not to have wives, children and grandchildren. Three young men, perhaps representative of the other 60,000 Australians whose lives were cut tragically short. But what of those who did return? They were certainly far removed from the young men who enthusiastically volunteered, most expecting an adventure. They saw and experienced horrific things that no one who wasn’t there can even begin to imagine. They had changed, their families had changed, the world had changed. In those days there was no term for post-traumatic stress disorder, nor any treatment. You just had to ‘man up’ and cope. Those who couldn’t cope took solace in alcohol, may have been prone to domestic violence and some took the option of suicide. One of the Glen Innes Heydon clan to be permanently changed physically and emotionally was the son, Robert W. Heydon who was wounded and returned after having one leg amputated at the thigh. BACK A COUPLE OF DECADES  Sarah’s eldest child, William, is the one who marries Amy Kneipp in 1883. William was ten years older and the following year, 1884, they also call the first born of 8 kids, William. The others were: Walter (Wattie) (1886) Cleave (1887) Mildred (Millie) (1889) Laura (1891) Harold (1893) Ida (1895) Frederick (1897) Their father, William, died in 1897, leaving Amy with 8 children aged 0 to 13 to raise while working the farm. The year Frederick was born and their father died George Reid was Premier of New South Wales. George would later become Prime Minister. He has nothing to do with the Heydon family tree but he would have been an entertaining bloke to invite over for dinner. He was a portly, rotund chap and a heckler on the hustings pointed at his ample paunch and cheekily asked, “What are you going to call it, George?” To which George replied, “If it’s a boy, I’ll call it after myself. If it’s a girl I’ll call it Victoria. But if, as I strongly suspect, it’s nothing but piss and wind, I’ll name it after you.” Of the daughters, Ida died aged 8, Millie died aged 12 and Laura died just shy of her 102nd birthday. The kids grew up on a property at Fladbury near Rangers Valley, about 25 miles (40km) from Glen Innes in a slab house. The walls were lined with newspapers for insulation and covered with hessian. The wall linings were a haven for all manner of reptiles. Amy, made all the clothes. The non-visible parts from white flour bags. Nothing was wasted. Everything was home-made or grown – the bread, fruit, vegetables, soap and candles. While artists like Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton were busy painting the Australian bush and poets like Banjo Paterson and Henry Lawson were writing about the bush, the Heydons just went about their way, living in the bush. The children walked about three-and-a-half miles (6km) to a small, one-teacher school. There were no roads, just a bush track that was home to snakes, lizards and goannas. The boys enjoyed picking up stray goannas and chasing the girls. The kids did their best to help Amy manage the property but the struggle proved too much and the family moved into town in 1900. William Francis was one of Sarah’s grandsons not to fight in World War One. As manager of the Glen Innes Butter Factory, his job would have been deemed an essential service to the community back home. Wattie also worked in the butter factory and he enlisted and went to fight as a Light Horseman in 1915, aged 29. Wattie saw the war out and was returned to Australia in June, 1919. Not a lot is known of his journey after that. It is thought that he helped out with mates who had been allocated soldier’s settlement blocks (farms) until 1934 when he relocated to Papua New Guinea to manage a plantation. Wattie was killed in a bombing raid in 1944 when the Japanese bombed civilians on Kavieng Wharf. The Japanese Rear-Admiral who ordered the bombing was tried for war crimes and was executed by hanging. Cleave also enlisted, as did Harold. Harold was wounded at Gallipoli and Cleave was gassed on the Western Front. EMILY JANE DAVIDSON Back to those Glen Innes women for a wee bit… Way back in the 1800s, Janet Graham married William Davidson and they had a son, Archibald Graham Davidson (1837-1905) who migrated from Scotland to Glen Innes. Arch married Mary-Ann McHatton (1843-1908) from Emu Creek, Walcha (160km from Glen Innes). They had 13 kids! Rabbits. One of them was Emily Jane Davidson (1883-1947). Above middle row, second left. Emily married William Francis Heydon in the Glen Innes Presbyterian Church in 1911 before moving to Bowraville and Tumut.  While in Bowraville they had three boys, Archibald William Davidson Heydon (1915), Harold Norman Heydon (1921) and Keith Heydon (1922). In 1925 they moved to Tumut, with William receiving a gold watch from his work inscribed, “Presented to W.F. Heydon Esq. by his friends on his departure from Bowraville 28.3.25.” In Tumut, William ran the co-op, or more specifically, the Tumut Co-operative Dairy Company Limited. Emily died in 1947 and William (Billy) married Elsa Rose McGruer in 1952. Elsa (1894-1976) had previously married David John McGruer and they had a son, John. John married Lorna and raised their family on a farm called Bonnie Doon at Brungle, halfway between Gundagai and Tumut. A nice man. A man of few words. He was a pallbearer at the funerals of William Francis and his son, Harold Norman, the father of Ian and Margaret. His mother, not so nice. Grandchildren, Ian and Margaret, knew Billy and Elsa as Pop and Gran. Elsa didn’t seem to like the grandchildren much. Or Harold. Or Jill. Or even Billy that much. Maybe people just irritated her or she just had what Jill would have said was an ‘unfortunate nature’. One afternoon, Harold was up from Gundagai in Tumut on business and he thought he would pay Billy and Elsa a visit, unannounced. He arrived at the house to find his blind father, outside in the rain, waiting for his wife to return home. When she returned by taxi, she said she had been to the shops. Harold let it go through to the keeper. Why upset the person who was caring for your invalid father? After Billy died it was discovered that ‘the shops’ was a euphemism for the RSL club. What was expected to be a substantial estate had disappeared. The whole estate had been squirted up the wall playing poker machines. See, just because people are part of your family, they don’t have to be nice! Back to Billy… Billy Heydon, as mentioned, was blind. This didn’t mean that life stopped. Even without sight he would mow his back lawn. He measured out the steps and distances methodically and filed them away in his amazing memory bank. It was frightening watching him push the mower at full tilt to pull up and turn just inches away from the shed or the fence. He also followed the horses on Saturdays. He didn’t bet on them, he just enjoyed picking winners. Thanks to the skill of race-callers like Ken Howard and Bert Bryant he could ‘see’ every race – their descriptive talents produced theatre of the mind – and he would lock away handy information on how horses performed. Before we move on to the next generation of Heydons, let’s have a quick look at a few of William’s other siblings… CLEAVE HEYDON Cleave Heydon married Florence Croft in Tenterfield in 1913. Florence was born in 1888 in Newcastle and died in 1983 in Tenterfield. Their children were Bruce (1929-1990), Caroline (1926, died at birth), Daphne (1923) and Marie (1921-2003). Marie did a lot of research into the Heydon family tree and had three children, two boys and Kay, who continued the research. Cleave and Florence also had two kiddies before Cleave went to war, Laureen Ethel in 1913 and Harold Cleave ‘Pat’ in 1915. Cleave was the last of the three to enlist, on April 12, 1916. He was a butcher, aged 27. On his attestation paper of enlistment he allotted three-fifths of his army pay to go to supporting his wife and children. While serving overseas, Cleave would buy postcards (carte postale) for the little ones when on leave and leave the simplest but warmest of messages like, “To dear little Laureen and Harold – love & XXXXXX.” There is also a delightful postcard sent from Florence to Cleave. On the ‘photo’ side is a young lady lifting her dress to reveal and ankle-length undergarment with the caption “Oh! You flirt” – on the reverse side Florence had written, “Remember me when far away, Remember me I ask each day, Remember me and all my lot, And then you will forget me not. From your loving sweetheart.” Cleave embarked as a private as part of the 4th Pioneer Battalion from Brisbane in September that year. Off the NSW coast Cleave wrote a note on a cigarette packet, put it in a bottle and tossed to over the side. On it he had written: “Transport at sea 21/9/1916. All is well at sea. To my dear wife, Mrs C. Heydon, Molesworth Street, Tenterfield NSW.” A Mr Nicolle of Lake Illawarra in N.S.W. found the bottle whilst walking along the beach near Port Kembla. His wife forwarded the message to Florence (Mrs C.), adding her own message, “I pray your husband will come through safely and be restored to you in good health.” Cleave came through safely and was restored to her only in adequate health, courtesy of two mustard gas attacks. He was awarded the Military Medal for bravery in the war. The citation reads: For coolness and devotion to duty during the operations on 8th August near MORCOURT S.E. of CORBIE. On approaching a ridge during the second phase of the operation near MORCOURT our troops came under heavy machine gun and rifle fire from a strong enemy detachment organised on the opposite hill top. L/ Cp. HEYDON, regardless of danger rushed forward with his Lewis Gun and dispersed the enemy thereby enabling the wave to continue without further casualties’. Cleave returned to Australia, from England, in June 1919. He was a blacksmith as well as a butcher and was a gentle, kind man with lots of time for his family. Cleave enjoyed horse riding and was handy wielding a stick because he believed that the only good snake was a dead snake. He died of lung cancer in 1953. This may have been attributed to his smoking (roll-your-owns) but the gas he endured on the Western Front was probably the main contributor. His beloved Florence lived another 30 years, dying in 1983, aged 95. But for the war they may have grown old together. This was the obituary to Cleave in the Warwick Daily News of November 19, 1953: WALLANGARRA: Mr.Cleave Heydon, M.M., of World War I, died in the Greenslopes Military Hospital, Brisbane, on Wednesday, November 11, after an illness extending over several months. The casket was brought to Wallangarra on the mail train on Saturday, and was taken to the R.S.L. Memorial Hall where it remained until Sunday afternoon, members of the R.S.L observing a solitary vigil over the casket. After a service conducted in the hall by the Wallangarra sub-branch R.S.L. and R.A.O.B. Lodge, of which deceased was also a member, the coffin was taken to the Union Church. The service was conducted there by the Rev. Lindsay, Church of England, Stanthorpe. The little church was packed with a large overflow outside. The funeral was one of the largest seen in Wallangarra and almost a mile long. At the Wallangarra cemetery, guards of honour were formed by Diggers and brethren of the R.A.O.B. Lodge. Mr. Lindsay officiated at the graveside. Of a quiet and unassuming manner, the late Cleave Heydon made many friends and was respected by everyone in the district. He helped all worthy causes and loved birds, animals, and wild flowers. In his day he was a very good horseman, and few horses could unseat, him. Born at Glen Innes in 1888, he came to Wallangarra in his early youth and followed a number of vocations until he retired from the Department of Agriculture and Stock, of which he was an inspector, last year. On January 15 1913, he married Miss Florrie Croft, of Tenterfield, and they made their home at Wallangarra’. Where, except for his World War I service, they have lived ever since. In 1914 soon after war was declared, he gave up a flourishing butchering business to enlist with the A.I.F., serving with the 4th Pioneers Battalion. As a Lance Corporal and Lewis gunner of 4th Pioneers, he was awarded the Military Medal in France in August, 1916. His platoon was almost cut off by the enemy. Standing by his Lewis gun, he kept the German hordes at bay, holding a bridge until the whole of his platoon could retire across the river. He then followed. He fought this delaying action with utter disregard for his own safety, his conspicuous bravery winning him the M.M.. Although he went through the whole of the European campaign without a wound, he was twice gassed. The effects of this hastened death. He returned to Australia in 1919 and lived here until his death. In World War II he was too old for active service, but was a prominent member of the V.D.C. He was a very keen “home man” and his family’s interests and welfare were always his first and constant thoughts. He leaves a widow, two daughters, Mrs. R. Ditton, and Mrs. L. Collins, of Wallangarra, two sons, Harold (Pat) of Wallangarra, Bruce of Riverton, eight grandchildren, and a huge circle of friends to mourn the loss of a typically fine Australian. HAROLD HEYDON  Harold Heydon was born on October 1893 to William Fitzgerald and Amy Heydon. He had five older siblings – Billy, Wattie, Cleave, Millie and Laura. Two more kiddies were born after him – Ida and Frederick. According to the Glen Innes examiner, Harold won a Sunday school prize in 1904, was handy at rifle shooting in 1908 and represented in football in 1909. He was a school cadet and on leaving school became a teacher. In 1914, less than a month after World War One began, he enlisted and embarked from Sydney on the HMAT A23 Suffolk in October as a Sergeant in the 2nd Battalion, C Company. According to the AIF records he was 21, single, nearly 5’10” tall and weighed 170lbs. As a Staff-Sergeant, Harold was the highest-ranking non-commissioned rank. He was wounded and returned to Australia before any chance of promotion. Also aboard the Suffolk was an officer, Captain George Lewis Blake Concanon, who was also known as Con. Aged 33, Con was an only child and was educated at Toowoomba Grammar School. Their battalion went to Egypt for training and on to Gallipoli. Both men hit those shores with the first wave of Anzacs, just before dawn on April 25, 1915. The campaign for both men was short. Captain Concanon was killed in action during a bayonet attack on April 26. He left behind a wife and two-year-old daughter. There is no known grave but he is honoured on the Lone Pine memorial. Captain Ken Millar would later write, in the RSL magazine Reveille (1932), that: Harold Heydon, now secretary of the N.S.W. Cricket Association, who was senior sergeant and was with Concanon the whole time of this fight, assures me that ‘Con.’ was wounded no fewer than four times in the two days. He applied field dressings and carried on! Eventually he sat down, with his back to a bush for support, and directed the fire until his final wound – a direct rifle shot in the forehead. Less than a month later, on May 20, Harold was seriously wounded in the leg and spent a deal of time in a hospital in Egypt before being returned to Australia for further medical attention. For the rest of his life, he walked with his leg in a brace and with the assistance of a cane. He died in 1967, aged 74. He was so proud of his service at Gallipoli that he personalised his number plate – HH701 – his initials and his regimental number.  On Harold’s return to Australia, his sister, Laura, went to Sydney to accompany him back to Glen Innes. This article is from the Glen Innes Examiner dated September 30, 1915 under the headline, ‘The Return of Sergt Heydon’ tells of a somewhat botched civic welcome: Yesterday morning the second wounded hero from the Dardanelles in the person of Sergeant Heydon (son of Mrs. Heydon of Glen Innes), arrived home. For some reason or other, there appears to be a deal of secrecy about these home-comings. It was rumoured on Tuesday afternoon that our wounded hero was to arrive on the following morning, but nothing authentic could be ascertained, consequently a number of people who would otherwise have been present to take part in the welcome were not present. However, there were couple of hundred in the vicinity of the station house when the train steamed in. It was thought the band would have been on the platform, as on the former occasion, to play a welcome “Home, Sweet Home”; but the fact of the train running to time may have had something to do with this, as the members of the band were not all in their places. Sergeant Heydon, who was accompanied by his sister, alighted from the carriage on crutches, and was met by his mother, the deputy-mayor, and town clerk. The young soldier, who participated in the famous landing, was wounded in the right thigh by an explosive bullet. He looked somewhat thin, and appeared to have had a rough time. He was escorted to the mayor’s car, where he was accorded a hearty welcome. In doing so, the deputy-mayor said Glen Innes could well feel proud of their soldier hero, whom he was pleased to extend a welcome on behalf of the citizens. The example set by Sergeant Heydon could well be followed by a number of other young men in Glen Innes, whose services were now needed at the front. Canon Kemmis also spoke a few words of welcome, after which cheers were given for Sergt. Heydon, Mrs and Miss Heydon, and the boys in the trenches. A procession, headed by the town band and members of the citizen reserves, was then formed, and marched to the town hall, at which point the motor car containing Sergeant Heydon and his party, drove on to his home. There is no getting away from the fact that there is a deal of laxity about welcoming home the returned soldiers; In fact, there is no system whatever. A few weeks ago, when Sergt-Major Knight returned, he was given a hearty welcome at the Town Hall, and a number of people naturally thought the same mode of procedure would be followed yesterday morning. Accordingly, they assembled at the Town Hall for that purpose, but the “powers that be” took a different attitude, and made the public welcome at the station instead, and then marched to the Town Hall, for what purpose it’s hard to say. In other towns these functions are carried out with a certain amount of decorum, the management being left in the hands of people who evidently understand their business, and the returned heroes are given a reception something after the kind they are entitled to. But they do things on a different scale in Glen Innes. However, it is to be hoped no further bungling will ensue regarding this matter, and that in future the welcome-home speeches will be made at the proper place— the Town Hall.  The shrapnel damage to Harold’s leg proved a slight hindrance for him executing his duties as Secretary of the New South Wales Cricket Association. The executive offices at the Sydney Cricket Ground were up in the Members Stand and it took considerable effort for Harold to get down the stairs to the player’s dressing room – so he tried to limit the trip to once a day. Not that the players would have minded – Harold wasn’t that popular with many of them. In fact, behind his back, he was given the nickname ‘The Fuhrer’. Harold’s tour of duty as staff-sergeant would have equipped him to be an able administrator with fine attention to detail, but he was an officious disciplinarian who sometimes lacked people skills. Each morning he would run his finger along the service counter in the bar and if it wasn’t spotless there would be hell to pay. He had a stretcher bed in his office, in case work ran into the evening. Each week he would put fifteen shillings in the bar till to cover his daily ration of ginger ale and Vincent’s powders (painkiller containing the addictive ingredient phenacetin, the forerunner to paracetamol). There were two things that stood out during Harold’s 24 years as the NSWCA Secretary – one was his signing of a promising young Bowral cricketer by the name of Donald Bradman… the other was not keeping Bradman ‘happy’ with a small pay rise and that was a decisive reason The Don left NSW to play for South Australia. Letting him go has to be the cricket version of the people who initially rejected The Beatles and J.K. Rowling. In the subsequent 14 innings for SA against NSW, Bradman made 1178 runs at an average of 130.9. In private, Harold married Constance (Connie) and they had a son, Ian, who was a handy cricketer at grade level. After his tenure with the NSWCA, Harold became President of the Killara Golf Club. It’s a fair guess that he accepted purely for administration reasons and not to play the game because we already know about his handicap, courtesy of Gallipoli. ARCH, HAROLD AND KEITH As mentioned, Archibald William Davidson Heydon was born in 1915, Harold Norman Heydon in 1921 and Keith Heydon in 1922. Arch married Pam Hart, who already had a daughter, Judith, and they had Vicki and Jacqui. Keith married Betty Robson and they had Peter and Debbie. Harold married Jill Learmont in 1946 and it will be best to swing across to the Learmont tree to pick up that thread. To wind up with World War Two – Arch and Keith enlisted. Arch was a commando and a sniper. Keith was assigned to a hospital ship that was bombed off Darwin. Harold tried to enlist in all three services, army, navy and air force, but was rejected on medical grounds with rheumatic fever is his back story (potential dodgy ticker). Arch and Keith found careers in the bank, both becoming managers who were posted to many locations including New Zealand and Alice Springs. Harold went into local government and became Shire Clerk of Gundagai, the youngest to achieve that position. And finally, a very special member of the family… LAURA HEYDON Laura Heydon was an intelligent, witty, strong, independent woman who never married but was never lonely. People who give of themselves never are. She once mentioned that had a beau when she was a young teacher, but he was killed in World War One. She died aged 101 and 10 months. Her 100th birthday at the Roseville Golf Club was the celebration of a life wonderfully lived. Even at that age she was an avid reader, a fabulous lunch companion and a formidable Scabble opponent. He motto in life was “life is too short for tepid food or tepid people.” Laura taught in Glen Innes and at a one-teacher school in Pallamallawa before moving to teach on Sydney’s north shore (Neutral Bay, Crows Nest, and Roseville). She was asked to retire from teaching in the 1940s for health reasons. She only had one kidney. Imagine the age she could have lived to if she had good health! For a detailed yarn about your scribe’s personal recollections of Laura, here is a link. |